The other day I found myself explaining the word ‘wont’ to someone. Not the contraction ‘won’t’, but rather its apostrophe-less unrelated twin:

Wont

adjective: accustomed, used, given, inclined. e.g. “As he was wont to do”

— New Oxford American Dictionary

In other words, the one almost no-one uses. I believe I was attempting to add a vaguely historical flourish to a comment I was making. Unfortunately the person I was speaking to was German, and wont turned out to be a word they hadn’t yet added to their English vocabulary (can’t blame them really).

So I found myself explaining the word ‘wont’. I knew its general meaning, but I couldn’t really communicate why it felt old-fashioned, and I certainly didn’t know its origins. It was just an “old word”.

I come across old words a lot, because, let’s face it, epic fantasy novels are riddled with them.

Why Does it Sound Old?

We generally recognise an old-fashioned word or turn of phrase when we encounter it. Some part of our brain registers that this is a word we usually only see in old books, period films, and certain types of fiction. These words can be fascinating: little relics that live on in our language today, throw-backs to old ways of speaking. However, we rarely have much idea of why a particular sentence or word sounds old.

So I decided, with the help of Susan Mandala’s insightful book Language in Science Fiction and Fantasy: The Question of Style to examine a few that get used in epic fantasy and science fiction:

(I’ve done my best to be accurate and thorough, but I’m not an expert linguist or etymologist, so if I’ve gotten something wrong, feel free to tell me and I’ll fix it up!)

1. “Anon” – Archaic Words

Sometimes the archaic feel in fantasy is achieved simply by using old, out-of-fashion words, words like wont, bade, fain, anon, smite, slain, hearken, fell, unto, thrice, prithee, forsworn.

Girt: The Unauthorised History of Australia (Penguin Australia)

In Australia, we’ve even got one in our national anthem: “our home is girt by sea”… which just feels odd when you have to sing it. This has recently been used, rather cleverly, as a title for a book on Australian history: Girt: The Unauthorised History of Australia.

It’s fascinating to explore the origins of some of these old words. For example, prithee is apparently a 16th century alteration of “pray thee”, and forsworn comes from the Old English forswerian meaning “swear falsely” or “abandon or renounce an oath.” If you want to find things like this out, it’s as simple as typing your ‘ye olde’ word into the Online Etymology Dictionary.

Speaking of which, “olde” is a “pseudo-archaic mock-antique variant of old” and was first used in the early 1900s. So the whole ‘ye olde’ thing… it’s not actually very old. It’s mock-old.

And if you’d like a list of some archaic English words, Oxford Dictionaries has created one.

2. “Be he living or be he dead” – Subjunctive

“If we be but a day away from our kind we are lonely”

— The King of Elfland’s Daughter, Lord Dunsany

Using “are” would be the modern thing to do… but ‘be’ just sounds so much more, well, old and weighty, doesn’t it?

So why doesn’t it just sound like bad English?

This is actually the use of a now largely obsolete form of the subjunctive mood. If you’ve ever learnt French, this won’t be such a foreign concept. The French language still makes regular use of the subjunctive. This mood is usually used to indicate uncertainty. So where “He is” (present indicative) suggests a known and objective fact, “He be” and “He were” (present and past subjunctive) suggest an uncertain or hypothetical state.

We still use the subjunctive in present-day English. For example: “He may be…”, “If I were you…”, “If he were to own…”, “run, lest she catch you”, “whether you be…”, “Suppose she were rich…”

However, particular forms of it are no longer in common usage, or to quote Mandala, they are “deviant”… which is why phrases like “whether it be the work of god or man” or “it were better if they had…” sound old-fashioned. Just like the fairy tale example I used above:

“Be he living or be he dead, I’ll grind his bones to make my bread”

— Jack and the Beanstalk

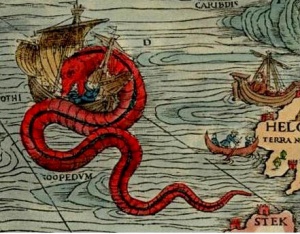

3. “Here be dragons” – Pirate-speak and Archaic Language

So what about the famous phrase on maps “Here be dragons”?

So what about the famous phrase on maps “Here be dragons”?

Is that subjunctive like the phrases above? Does it suggest there may or may not, in fact, be dragons there?

Well, opinions seem to vary on this one, but from what I gather, it isn’t subjunctive.

This is apparently just an archaic form of the present tense. In other words, this is just an Early Modern English way of saying “are”, one we still retain in phrases like “the powers that be”. It’s also worth noting that the only two known historical uses of the phrase “here be dragons” were in Latin: HC SVNT DRACONES (i.e. hic sunt dracones: here are dragons). So “here be dragons” is simply an archaic English equivalent.

You might also have noticed that all this use of “be” is a little reminiscent of pirate speak, e.g. “Aye, ye be a scurvy dog”.

Interestingly, our idea of how pirates speak has little to do with how historical pirates actually spoke, and much more to do with Robert Newton’s portrayal of Long John Silver in Disney’s Treasure Island (1950). The actor used his local accent (from south-west England) and the impression stuck. (For more on this, and on the many other things we get wrong about pirates: Aye Before E, Except After Sea).

Regional English dialects often retain some of the archaic pronouns and conjugation no longer used in mainstream English (See: Grammar in Early Modern English). So the ‘ye be’ of the pirate is indeed an example of an archaic form, but it seems to have only become associated with pirates due to its retention in regional dialect.

4. “Unsavoury louts they were” – Word Order

Yoda (Star Wars Wikia)

Sound vaguely Yoda-esque?

When Yoda speaks, he regularly places the subject and verb at the end of the sentence. However, this disruption of the subject-verb-object word order we’re used to in present-day English is not a Star Wars invention.

While not doing it in exactly the same way as Yoda, many fantasy stories invert word order to echo the different word orders that were prevalent in Old English. Take for example these lines from the Old English poem Beowulf (a great influence on J.R.R Tolkien) and their literal translation. You can see how the verb is placed at the end of the clause:

Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum

monegum mægþum meodosetla oftēah;

egsode eorlas, syððan ærest wearð

feasceaft funden;Often Scyld, Scef’s son, from enemies’ bands

from many tribes, mead-benches seized;

terrorized earls, since first he was

destitute found;— John Porter, Beowulf: Text and Translation

Here are some of the examples Mandala gives of deviant word order use in fantasy novels:

- shrewd was he; – The Lady of Sorrows, Cecilia Dart-Thornton

- rugged and rocky was the coastline. – The Lady of Sorrows, Cecilia Dart-Thornton

- high soared the dragon; – Elric, Michael Moorcock

- hilt-deep the sabre sank; – Conan the Adventurer, Robert E. Howard

Mandala also points out that sometimes fantasy writers will use the word there as ‘dummy’ subject at the beginning of a sentence, in order to place the real subject near the end of the sentence, mimicking a similar construction in Old English:

There came up to him from far below, shrill and clear in the early morning, the sound of his peacocks calling

— The King of Elfland’s Daughter, Lord Dunsany

5. “Your Grace” – Titles and Forms of Address

Since epic fantasies are often filled with royals and monarchical systems, and are rather nobility-obsessed (as I pointed out in a previous post), it’s no surprise they make use of archaic titles and forms of address. In the novels Mandala analysed, people are often referred to as:

King Uther from the TV Show Merlin

- Lady

- Lord

- Your Grace

- My Lady

- My Lord

- Master

- Sir

- Friend

- Good _______

- Dear _______

“Good” and “dear” were often added before a title to politely address a stranger e.g. “good sir” (Elric) and kinship terms such as “father, sister, brother” were used as terms of intimate address.

Another interesting technique Mandala points out is the display of “severe submission and extreme distance” by using third person address. In The Lady of Sorrows this is used by the maidservant before she forms a closer relationship with the protagonist:

“Does my lady wish that I should soap her back?”

— The Lady of Sorrows

In modern English we would rarely use such ultra-polite, deferential language, but in fantasy novels these more archaic polite forms work well to suggest a society more reminiscent of a feudal England, with servants and nobility.

More Next Week

As these archaisms sucked me into a vortex of researching, I realised there were more than I could tackle in one post, and many were too fascinating to ignore. So come back next Monday for some hithering and thithering, thouing and theeing, and maybe even some bethwacking.

**This post is continued here: 6 More Archaisms and Why Authors Use Them**

It is my understanding that “ye” is a plural form of “you.” So when heralds call our “hear ye, hear ye,” what they’re saying is, “Everybody listen!”

LikeLike

Ah yes I forgot about “hear ye, hear ye”! I was reading up about ‘ye’ the other day actually. Apparently it was the plural form for centuries, then also started getting used as a polite singular form (and morphed into you), and then eventually completely replaced the singular ‘thou’. I often think it’s a shame we no longer have a unique second person plural form, and have to make do with things like “you all”.

LikeLike

There be archaic words explained here! Great post, can’t wait to read more next week.

LikeLike