Last week I listed some English archaic forms often seen in epic fantasy novels: things like “here be dragons” and “unsavoury louts they were” and “prithee”. This week I’m continuing with a few more ‘ye olde’ words fantasy authors like to throw into the mix, as well as having a look at why they do it.

So without further ado, and again with the help of Susan Mandala’s Language in Science Fiction and Fantasy: The Question of Style, here are the remaining 6:

6. “Winter is Come” – Using Be Instead of Have

In English, you could say both “the time has come” and “the time is come”… but the second one sounds a little more unusual, a little older.

This is because in the past, the verb “to be” was used for certain constructions for which we would now use “to have”. Other examples like the phrase above include “I am come”, “the time was come”.

A similar case of this switching back to the old use of the ‘to be’ word is in passive voice constructions:

Huon is driven forth! (instead of Huon has been driven forth)

You are discovered. (instead of you have been discovered)

– The Lady of Sorrows

So in Game of Thrones, we’ve known “winter is coming” for quite a while… but when winter finally comes, well, the Starks (if any survive) are just as likely to say “winter is come” as “winter has come”. I must confess I haven’t read all the books, so I don’t know if such a line has occurred yet or is likely to occur. If it does, I’ll be curious to see which one it is.

7. “Bethwack” – The Be- Prefix

Yes. Bethwack is a word. It meant “to thrash soundly” and was used in the 1500s. As far as I know, no fantasy novels have yet made use of this delightful word.

The be- prefix was apparently particularly used to produce words during the 16th & 17th Centuries, and a lot of those words still survive in present-day English (According to: Online Etymology Dictionary & English Language and Usage).

Some are considered quite normal:

befriend, bewitch, behold, believe, belong, behead

Some sound distinctly old fashioned:

besought, beget/begotten, bespoke

And some are just plain weird, and have not survived in present-day English:

bethwack, betongue “to assail in speech, to scold”.

Bespoke is an interesting one, as it is often used incorrectly. Bespoke means “custom-made” or “made to order”, in the sense of “spoken for, arranged beforehand”. Presumably, because of its old-fashioned-ness, some companies have started using it in their names and advertising, for example “bespoke books”, when their products are by no stretch of the imagination custom made (as this post on Gawker laments).

While fantasy novels often use the more old-fashioned be- forms, unsurprisingly, they tend to avoid the completely obsolete ones. Somehow I don’t think someone betonguing someone else would go down so well in a modern fantasy novel…

8. “Hither and Thither” – Adverbials and Demonstratives

These ones are a sure fire mark of oldness: hither, wither, thither, thence, whence, hence, yonder

But what, exactly, are these old things, and why do we have them, if we now just use here and there and where?

Well, again this is a remnant of an older form of English, where instead of just adding the prepositions “to” and “from”, we used these adverbs:

Wither: to where? (e.g. wither are you going?)

Whence: from where? (e.g. whence do you come?)

Hither: to here

Thither: to there

Hence: from here

Thence: from there

We still retain some of these forms in present-day English in words like henceforth (literally: from here onward).

And fantasy novels and films still use them:

“The Ring was made in the fires of Mount Doom; only there can it be unmade. It must be taken deep into Mordor and cast back into the fiery chasm from whence it came.”

— Fellowship of the Ring (Film)

Hugo Weaving as Elrond in The Fellowship of the Ring, Wikipedia

Interestingly, this line uses “from” as well as “whence”, which isn’t really necessary as whence already incorporates “from”. I’d hesitate to proclaim this grammatically incorrect because I’m no expert, but this article suggests that not only is this wrong, but this is an error English speakers have been making for quite a long time.

Regardless, the whence is in this line of dialogue for one reason alone: to make Elrond’s statement sound that little bit more grand and old and important.

9. “Thou & Thee” – Formality

Perhaps it’s a little too Shakespearian, or too jarring and evocative of religious texts, but I don’t see a lot of epic fantasies blatantly using ‘thou’ and thee’ anymore. Cecilia-Dart Thornton’s Bitterbynde trilogy, however, did make quite extensive use of these forms of address, as did Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings Trilogy… for example when the Nazgûl speaks to Éowyn:

Come not between the Nazgûl and his prey! Or he will not slay thee in thy turn. He will bear thee away to the houses of lamentation, beyond all darkness, where thy flesh shall be devoured, and thy shrivelled mind be left naked to the Lidless Eye.

— The Return of the King

So historically:

Ye was the plural form of ‘you’, and was used to speak to a group of people. In the 15th–17th Centuries, it was also used as the more polite, respectful form for addressing one person.

Thou was the singular form of ‘you’, used to address one person. In the 15th–17th Centuries, it was considered the less polite, more intimate/informal form.

Eventually “ye” became “you”, and this more respectful “you” form drove out nearly all uses of “thee” and “thou” (Thou, Thee and Archaic Grammar). Funnily enough, modern slang inventions like y’all, you guys and youse are an attempt to deal with our lack of a plural second person pronoun.

thou art – you are

thou be/beest – you be (subjunctive, e.g. “should you be willing”)

thou wast – you were

thou wert – you were (subjunctive, e.g. “if you were my friend”)

thou hast – you have

he/she hath – he/she has

While I don’t often see ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ used in fantasy today, the old inflections from the same period -(e)st and -(e)th crop up occasionally: doth, hath, sayest etc.

“unholy horn doth sound”

— Elric, Michael Moorcock

And even if we don’t see fantasy characters regularly using these forms nowadays, I think they’re still likely to live on in the snippets of invented poems, songs, legends and historical/religious writings that crop up in fantasy novels. It’s an effective way to suggest the historical language of a fantasy world, because we associate it with the historical language of our own world.

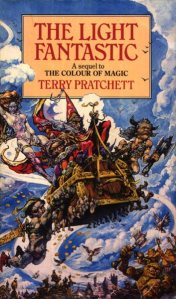

10. “The Light Fantastic” – Repositioning Modifiers

Sometimes fantasy novels make things sound old or grand by placing an adjective after the noun it modifies, rather than in front of it, as is the tradition in present-day English.

a field untended – The King of Elfland’s Daughter

(instead of an untended field)

champion eternal – Elric

(instead of eternal champion)

The Light Fantastic by Terry Pratchett, Book Cover

And you can see this in the title of Terry Pratchett’s comic fantasy novel The Light Fantastic, which is actually a quote taken from John Milton’s poem L’Allegro, published in 1645.

For some reason that simple shifting of an adjective can suddenly make something sound grander, more mythic, more old, especially when the adjective is something like everlasting or eternal.

“Love everlasting” sounds perhaps, like it might just last a little longer than “everlasting love”…

11. “Begone you creatures!” – Imperatives and Questions

Of course, commands like “begone” and “avaunt” are archaic in themselves. They’re perfect for fantasy wizards or witches or warriors to shout with gusto, to command evil spirits or demons:

“Begone, foul dwimmerlaik, lord of carrion! Leave the dead in peace!”

— Éowyn speaking to the Nazgûl in The Return of the King

However, even ordinary-sounding verbs like “know” and “go” can be made to sound archaic in the imperative (i.e. as commands), simply by stating the subject:

know you this

go you then

begone you creatures

Where in present-day English we would simply omit the subject.

Questions and imperatives can also be made to sound old by omitting the auxiliary ‘do’ where present-day English would require it:

How fares our master? — The King of Elfland’s Daughter

Speak not too hastily — Elric

I know not (instead of: “I don’t know”) — Conan the Adventurer

Let not the two touch — The King of Elfland’s Daughter

Do All Epic Fantasies Use Archaisms?

After going through all these archaisms, I think it’s important to point out that not all epic fantasy authors use them. Many simply use a more formal register of present-day English, so that the language doesn’t jarringly remind us of our contemporary culture but still sounds normal. For example, you won’t see many epic fantasy characters saying things like “cool” and “what’s up?”. This kind of informal language is more the realm of contemporary fantasy.

It seems that heavy use of archaisms in fantasy may be going a bit out of fashion, and fantasy films certainly tone down the archaic language. Take, for example, this scene from Peter Jackson’s The Return of the King, and the corresponding scene in the book:

Come not between the Nazgûl and his prey! Or he will not slay thee in thy turn. He will bear thee away to the houses of lamentation, beyond all darkness, where thy flesh shall be devoured, and thy shrivelled mind be left naked to the Lidless Eye.

A sword rang as it was drawn. “Do what you will; but I will hinder it, if I may.”

“Hinder me? Thou fool. No living man may hinder me!”

Then Merry heard of all sounds in that hour the strangest. It seemed that Dernhelm laughed, and the clear voice was like the ring of steel. “But no living man am I!”

— The Return of the King

The film version of the scene strips away pretty much all of the archaisms, from adding the modern ‘do’ construction back into the “Come not between…” line, right down to reordering Eowyn’s final line to be: “I am no man” rather than the original “no living man am I”. I guess some archaisms are just too awkward to hear spoken aloud these days.

Why Do Fantasy Authors Use Them?

When fantasy authors do, however, choose to use archaisms like the ones I’ve listed above, there are clearly a few reasons why they’re doing it. Some that come to mind straight away are:

- to suggest an old medieval era

- to evoke a general feeling of otherworldliness and separate the fantasy world from our modern world and culture

- to give the tale the flavour of legend, myth and fairy tale

And one that I had to admit I hadn’t thought of, but that Mandala highlighted:

- to suggest not just the past, but a whole past speech community with a different social hierarchy, different ways of showing respect/politeness/formality, and different ways of conveying the changing degrees of intimacy in character relationships

Historical Accuracy

When fantasy authors use archaisms, it’s worth mentioning that they’re generally not being historically accurate. By this I don’t mean that they use fake archaisms (though I’m sure that happens), but that their use of the archaisms is chronologically contradictory.

For example, a fantasy author might use an archaism that fell out of common usage by the 17th Century, together with an archaism that only came into use after the 17th century. They might invent a fantasy world reminiscent of the Early Middle Ages, but use words and forms that didn’t come into use until the Late Middle Ages.

Ultimately, this doesn’t really matter, because it’s not about being historically accurate. The point is to create the feel and flavour of a past world, not an accurate representation of it.

Is it Cheesy?

Some people will argue that archaisms in fantasy are cheesy or clumsy – a cheap trick where authors scatter about a few old words and some old-fashioned grammar. But as Mandala points out, many fantasy authors have made skilful and consistent use of archaisms, and use archaic language to add nuance and depth to their story.

As a writer, using archaisms is not easy… it requires you to put your everyday language aside and retrieve older forms of speaking… and not only that, but to do it correctly and consistently, and weave it into the narrative so it doesn’t sound jarring to the reader. So while I probably wouldn’t have the patience or the inclination to use archaisms in my own writing, I admire authors that manage to do it well.

The thing with thee/thou/thy and other archaic language is that they’re confusing. Although, as you say, they conjure up great pictures of a bygone era, I find it difficult to keep that up for very long.

LikeLike

Yes that’s always a danger – too much archaic language and you might just confuse people. Particularly with thee/thou, it’s a hard thing to sustain… Perhaps best used sparingly. Personally, I don’t think I’d be game enough to use it at all… Hard to pull off, and I might just end up confusing myself or doing it wrong!

LikeLike

Excellent article! Haha, “Bethwack” – I’m tempted to slip it into one of my stories now. 😉

LikeLike

Thanks! Now I’m actually trying to imagine “Bethwack” slipped smoothly into a story… I did find some old (though slightly odd!) examples: https://www.wordnik.com/words/bethwack 🙂

LikeLike

The thing is when Tolkien does it, it’s done with rhyme and reason and there is a specific purpose to it. The bit with Eowyn and the Nazgul for example – notice that Eowyn herself doesn’t say ‘thee’ or ‘thy’, she just says ‘you.’ The Nazgul are former Kings from the Second Age, it makes sense that they would speak differently and more archaically. It’s a technique that really works if you use it precisely as Tolkien did, and it really gives the narrative some depth of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved this post – and “bethwack”!

One small point: “ye” was the plural second person, rather like the US “y’all” or the New Zealand “yous” (and do you use “yous” in Australia as well?). “You” was the polite second person singular, with “thou” being the less formal and more intimate version. This sort of pronoun system is alive and well in other languages but we’ve mostly lost it in English… unless you are used to Shakespeare and the Old King James Version of the Bible.

Tolkien was very deliberate about when he used “thou” and when he used “you”, and explains this in, I think, one of the appendices.

LikeLiked by 1 person